[[{“value”:”

The minutes mentioned it. New York Fed’s Perli added some background. The Fed will likely provide details at its March meeting.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

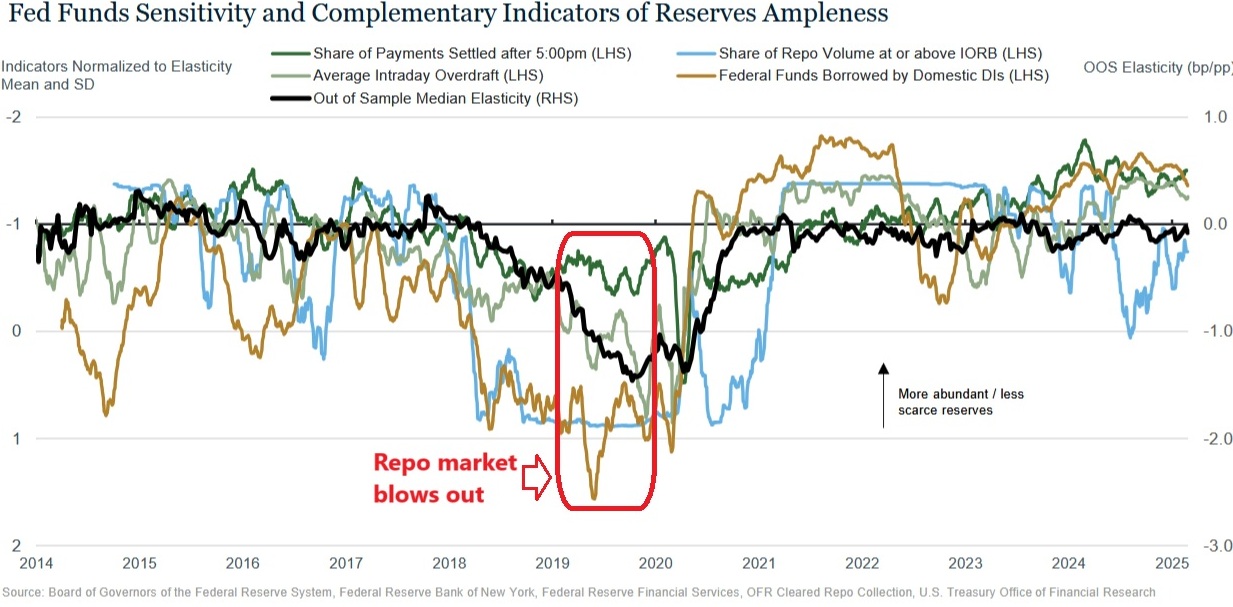

No one has ever drained $2.2 trillion in liquidity through QT from the financial markets, as the Fed has done since July 2022, and there is no playbook to go by. Withdrawing liquidity too fast can cause some places to run dry while others are still awash in it. Normally higher yields cause liquidity to move where it’s needed, but if it drains too fast, there may not be enough time for yields to do their job distributing liquidity, and then something blows out, like the repo market did in 2019. An accident like that would cause QT to stop. And the Fed has consistently said it wants to avoid another accident, which is why it slowed QT in June 2024 so that QT can keep going further.

And now there’s a new potential issue for the Fed – for its balance sheet and liquidity in the financial system: the debt-ceiling fight and the $800-billion checking account of the federal government. When $800 billion in liquidity suddenly pours into financial markets and then vanishes from the financial markets even faster, it moves the needle.

The first official mention came in the minutes of the January 28-29 FOMC meeting: that the FOMC is considering “pausing or slowing balance sheet runoff until the resolution of this event.”

So, not stopping QT entirely, but pausing or slowing it temporarily until the issues of the debt ceiling are resolved.

Then on March 5, the New York Fed’s Roberto Perli, Manager of the System Open Market Account (SOMA), which handles the Fed’s securities transactions, gave a speech about the more distant future of the Fed’s balance sheet, which paralleled what Dallas Fed President Lorie Logan had said a month earlier [Future of the Fed’s Balance Sheet: How Assets Might Shift from Longer-Term Securities to Short-Term T-Bills, Repos, and Loans after QT Ends. MBS Entirely Off the List]. But Perli included a detailed discussion about the near-term issue related to the debt ceiling.

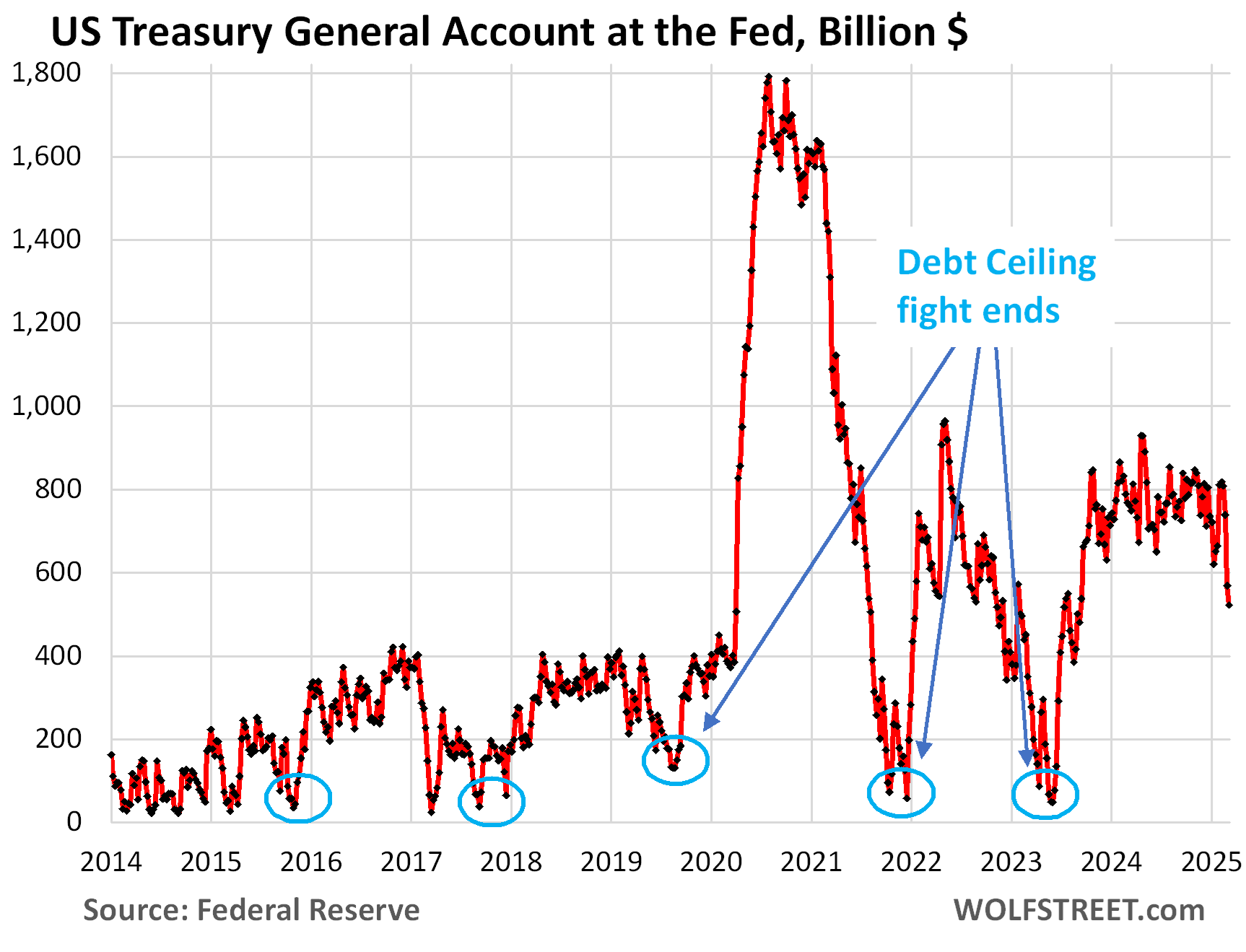

While the debt ceiling is in place, the government cannot raise more cash by issuing new Treasury securities and instead will run down its checking account at the Fed, the Treasury General Account (a liability on the Fed’s balance sheet).

Before the debt ceiling was reached, the TGA had a balance of over $800 billion, which is what the Treasury Department normally wants to keep in it. While the debt ceiling persists, that balance will be drawn down. It has already been drawn down to $530 billion. In past Debt-Ceiling fights, it was drawn down to near zero.

Drawing down the TGA effectively injects liquidity into the financial system, potentially close to $800 billion. But that’s not the problem.

The problem occurs when the Debt Ceiling gets lifted, and the government refills the TGA rapidly by issuing lots of T-bills, which sucks that liquidity back out of the financial system, and very quickly.

Last time, $500 billion got sucked out of the financial system in eight weeks in June and July 2023, and another $300 billion got sucked out over the next 12 weeks, to refill the TGA back to $800 billion by mid-October 2023. That was a lot of liquidity to vanish from the financial system in a short time.

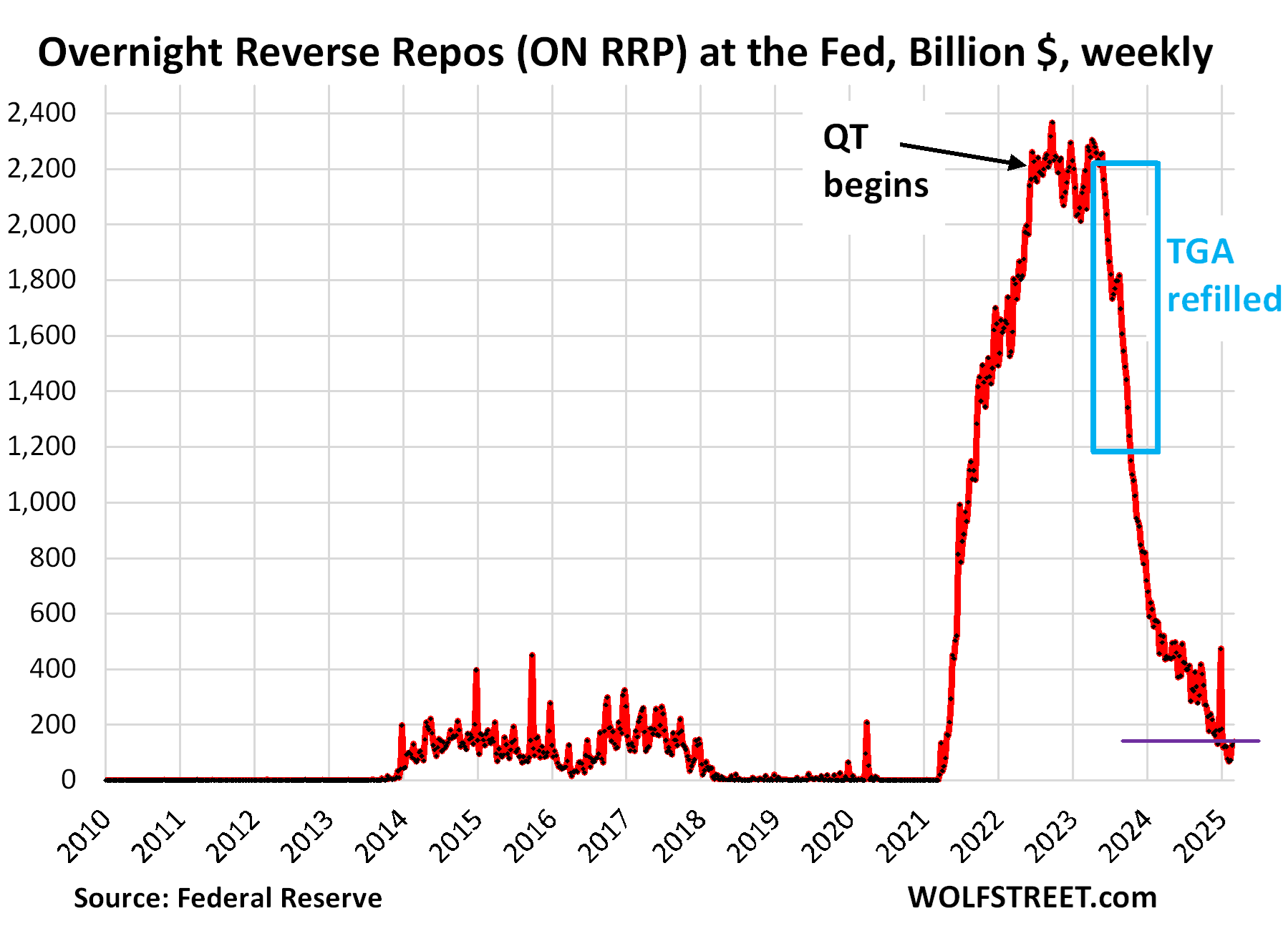

Last time, the overnight reverse repo (ON RRP) facility at the Fed, by which money markets deposit unneeded cash at the Fed to earn some interest, still had $2.1 trillion in balances, and that’s where the $500 billion came out of in June and July 2023, and the $300 billion in August to mid-October 2023.

It was smooth: Money market funds bought the massive amounts of T-bills the government issued during the TGA refilling process and paid for them with cash they got from exiting their ON RRP positions at the Fed. The cash went from the Fed’s ON RRPs via the money markets to the TGA. Both the ON RRPs and the TGA are liabilities on the Fed’s books. It didn’t impact the Fed’s assets. And it didn’t impact banking liquidity. It was unused cash from money market funds that funded those T-bill sales.

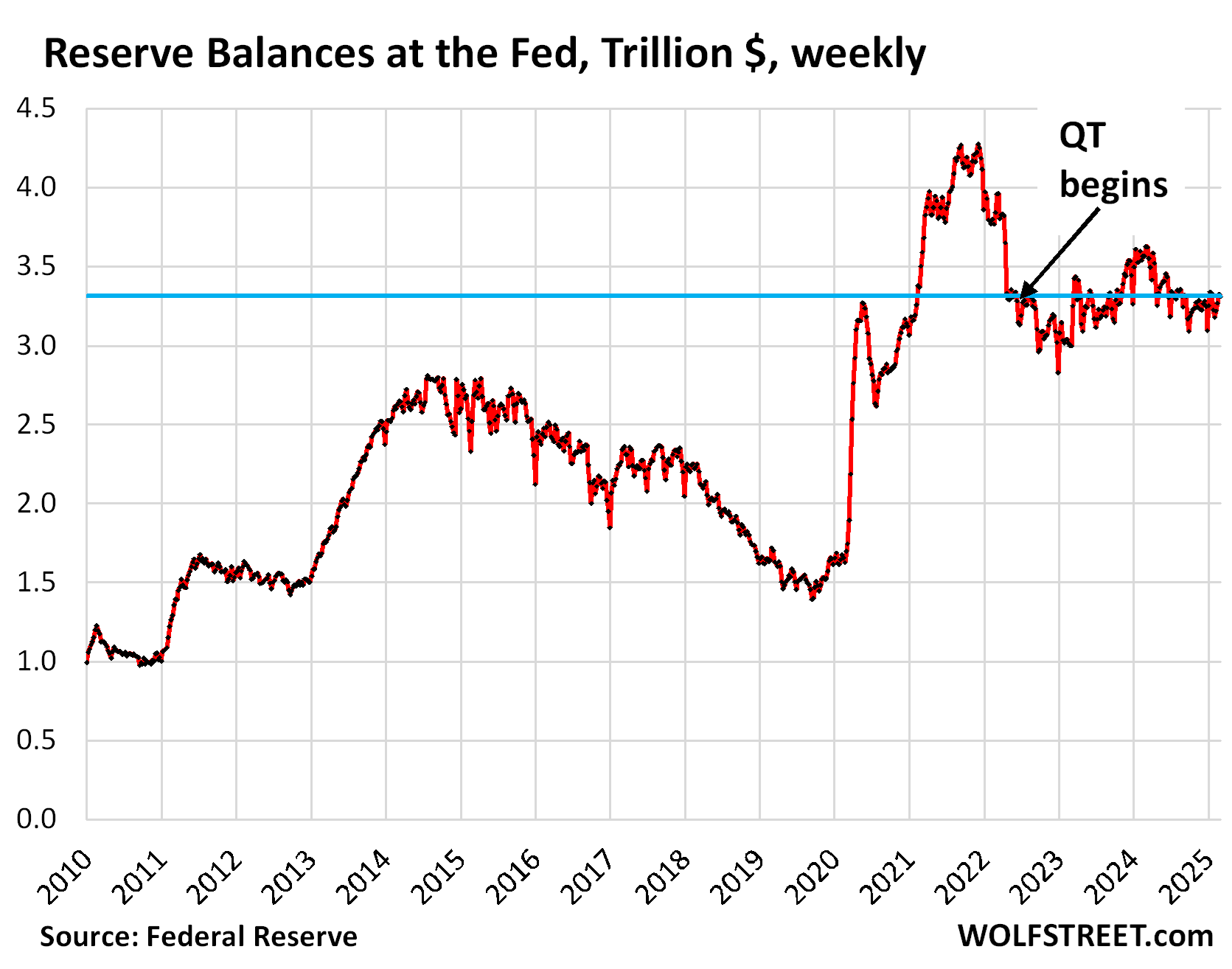

But this time around, QT largely drained ON RRPs and is starting to drain liquidity from the banking system.

The banks keep large amounts of cash on deposit at the Fed in their “reserve accounts,” as the Fed calls them. With these reserve accounts, the Fed acts like a central clearing place for bank transactions. Banks pay each other on a daily basis through their reserve accounts at the Fed. Huge amounts of cash flow through these reserve accounts every day. In addition, banks keep substantial amounts of cash in their reserve accounts for financial stability purposes, because it is the most liquid cash.

These reserve balances are what the Fed is trying to reduce with its QT. And they haven’t come down yet at all because all of the QT came out of the ON RRPs, and now, during the Debt Ceiling, liquidity is moving from the TGA to reserves.

So now, that liquidity needed to buy the $800 billion in T-bills that the government will issue to replenish the TGA will largely come out of the banking system – including reserve balances.

But the TGA is also now draining due to the debt ceiling, and part of that liquidity is going into the reserves, thereby temporarily covering up the drain on reserves from QT.

And this liquidity from the TGA now pouring into reserves is obscuring the effects of QT on reserves – that’s what the Fed is fretting about.

After the debt ceiling is resolved, the government will refill the TGA quickly, and this sucks liquidity back out of reserves, very fast, much faster than QT, potentially hundreds of billions of dollars in weeks.

The Fed is worried about the speed with which this happens after the debt ceiling, and that its signaling system – such as surging yields and spreads related to repo markets – will warn of reserves being low enough (near “ample”) in real time, rather than in advance.

By which time it may be too late, and liquidity demand could cause some major gyrations in the money markets, similar to the repo-market blowout that occurred in the fall of 2019.

In his speech, Perli noted that reserves are still “abundant,” and not yet near “ample,” but noted that “there is evidence that pressures in the repo market have been gradually increasing.” And he added, “For now, these signals from the repo market suggest no cause for concern.”

And he said with regards to the rates and spreads they’re following:

“With the partial exception of the repo indicator, these measures are currently all toward the top of the chart, and about in line with their benign levels of a year ago.”

“On the other hand, you can see that during periods when reserves were becoming less ample, as was the case in 2018 and 2019, these indicators tended to show movement and were further toward the bottom of the chart.”

This is the chart he referenced. I added the red box to show the period when trouble in the repo market arose after QT drew down reserves (click on chart to enlarge).

“Pausing or slowing balance sheet runoff until the resolution of the debt ceiling situation.”

To forestall a blowout in the repo market or other segments of the money markets, the Fed said in the minutes that it is considering “pausing or slowing balance sheet runoff until the resolution of this event.”

Perli provided some details in his speech and repeated the language from the minutes:

“Sharp and sudden changes in the supply or demand for reserves [through the TGA getting drained and then refilled] could in principle prompt reserve conditions to shift rapidly, depriving our indicators of much of their early warning potential. One factor that could lead to large and relatively fast swings in reserves is dynamics related to the federal debt limit.”

“Put simply, the longer balance sheet runoff continues while the debt ceiling situation persists, the higher the risk that, upon the resolution of the debt ceiling, reserves could rapidly decline to levels that could result in considerable volatility in money markets. “

As noted in the minutes of the January 2025 FOMC meeting, various participants thought it may be appropriate to consider pausing or slowing balance sheet runoff until the resolution of the debt ceiling situation.”

The back-to-back announcements about “pausing or slowing balance sheet runoff until the resolution of the debt ceiling situation” indicate that the Fed will provide further details fairly soon, likely on March 19, after the FOMC meeting.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

The post Why the Fed Considers “Pausing or Slowing” QT “Until the Resolution of the Debt Ceiling Situation” appeared first on Energy News Beat.

“}]]

Energy News Beat