[[{“value”:”

After inflation, “real” yields on money-market funds are near 2%, and households kept pouring cash into them. But CDs lost ground.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

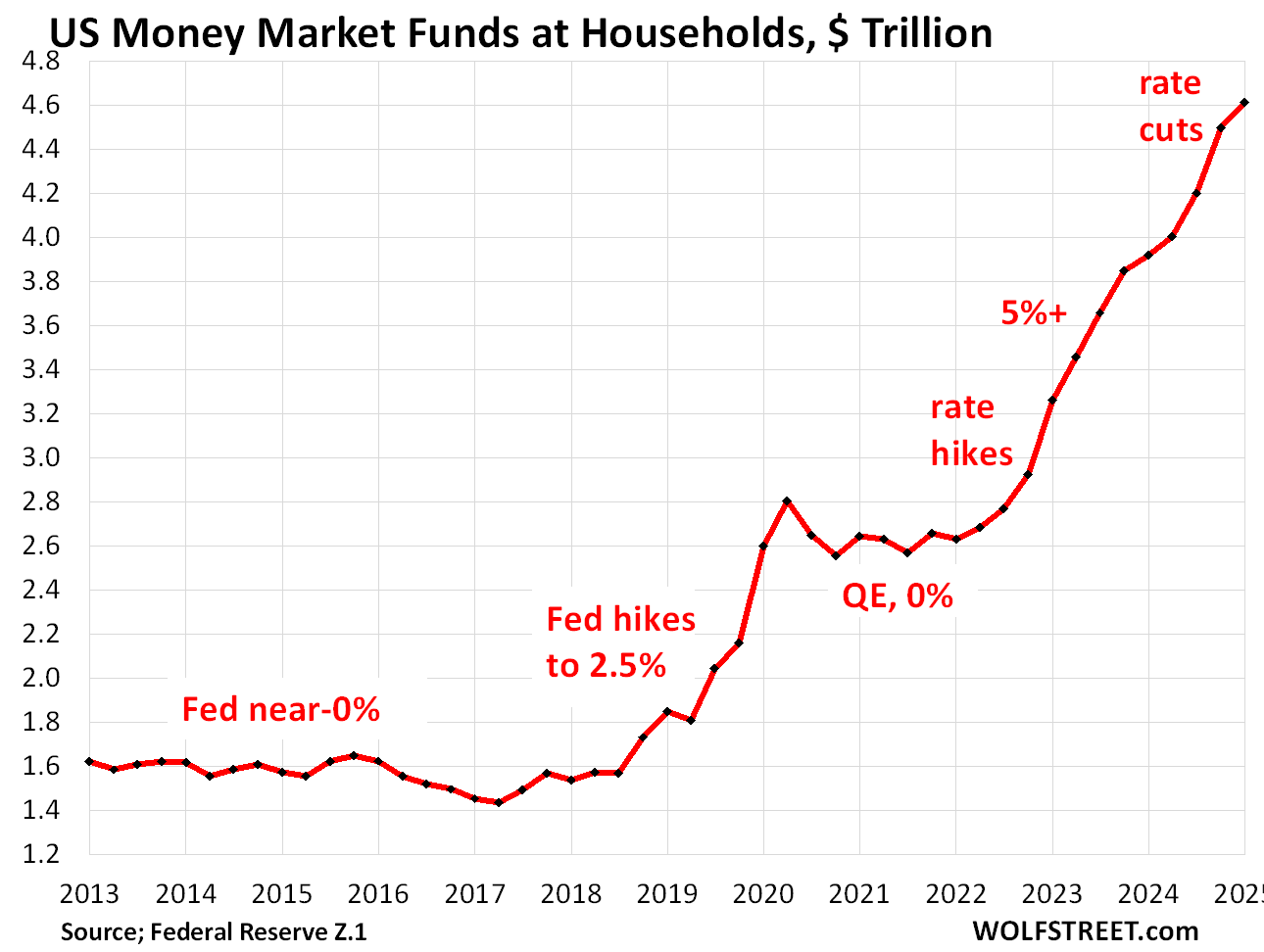

Balances in money-market funds held by households at the end of Q1 continued their massive surge and rose by another $115 billion from the prior quarter, to $4.62 trillion, and were up by $696 billion year-over-year, according to the Fed’s quarterly Z1 Financial Accounts today. Since Q1 2022, when the Fed started hiking its policy rates, balances have surged by $1.99 trillion.

The three-month Treasury yield is still at 4.36% currently, and has been in this range since the last rate cut in December. Yields of money-market funds (MMFs) closely track the three-month Treasury yield and remain in the 4.2% range, give or take, and are well above the current inflation rates, with CPI inflation at 2.4% in May. This puts the “real” yield on liquid ultra-low-risk cash at just under 2%, which seems to be an attractive proposition, and households keep pouring their extra cash into them.

These MMF balances include retail MMFs that households buy directly from their broker or bank, and institutional MMFs that households hold indirectly through their employers, trustees, and fiduciaries who buy those funds on behalf of their clients, employees, or owners.

MMFs invest in safe short-term instruments, such as Treasury securities with less than one year to run, much of it with less than six months to run, in high-grade commercial paper, in high-grade asset-backed commercial paper, in repos in the repo market, and in repos with the Fed.

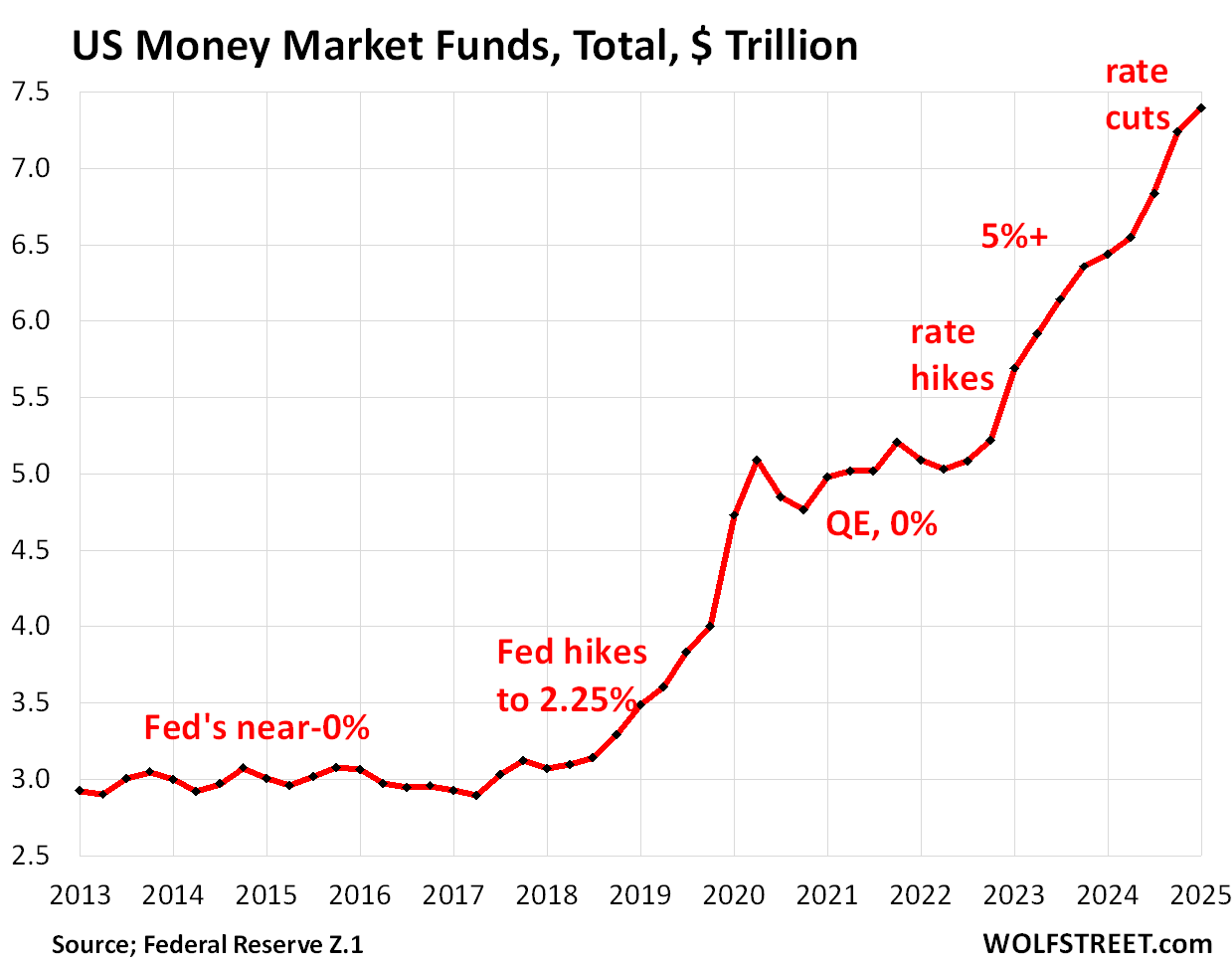

Total MMFs (those held by households and institutions) rose by $155 billion in Q1 from Q4, and by $957 billion year-over-year to $7.40 trillion. Since Q1 2022, balances have ballooned by $2.31 trillion.

MMF balances balloon with higher interest rates. When rates were near 0%, balances remained roughly stable for years at about $3 trillion. There is always some need for liquid cash even if it doesn’t yield anything. When the Fed hiked rates in 2017-2018, to ultimately 2.25%, $2 trillion of cash poured into MMFs. When yields started rising again in 2022 after the pandemic-era interest-rate repression by the Fed, MMFs ballooned by another $2.3 trillion. Higher yields bring a tsunami of cash to money-market funds.

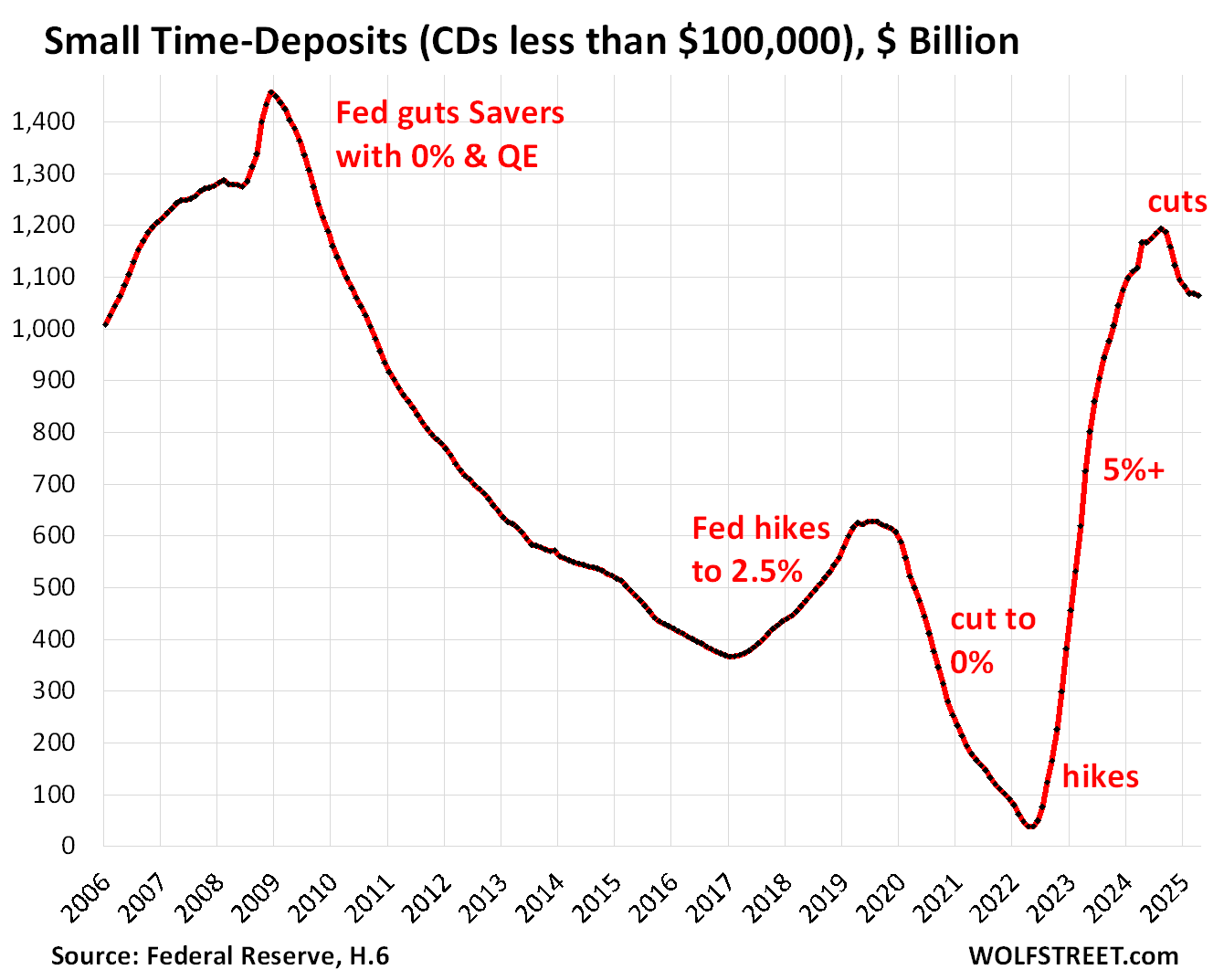

Small Time-Deposits (CDs of less than $100,000) have remained essentially unchanged at $1.06 trillion over the three months through April, after dropping from their highs in August 2024 of $1.19 trillion, according to the Fed’s latest Money Stock Measures.

But note the explosion of those balances as the Fed started hiking its policy rates: they went from near-zero in April 2022 to $1.19 trillion in August 2024.

These small CDs reflect regular savers. When the Fed gutted savers’ cash flow from savings in 2008, they began spurning CDs, and by mid-2022, small CDs had nearly vanished.

Banks only pay interest if they have to. For banks, deposits are loans from customers that form the banks’ primary funding. Paying higher interest rates on deposits increases a bank’s cost of funding, and lowers their net interest margin (net interest income minus the interest paid depositors and other sources of funding). So they offer higher rates only if they have to attract new deposits or retain deposits from existing customers. Bank accounts that provide essential services, such as transaction accounts, attract cash at near 0% because customers need those services.

Banks rely on deposits being generally “sticky,” especially in transaction accounts, and they expect when rates rise, that a big portion of deposits stays put even with near-0% rates. But as we can see in the CD charts here, CDs are not sticky, and they include brokered CDs sold through a brokerage firm; they’re like hot money that can leave at the end of the term if rates are too low.

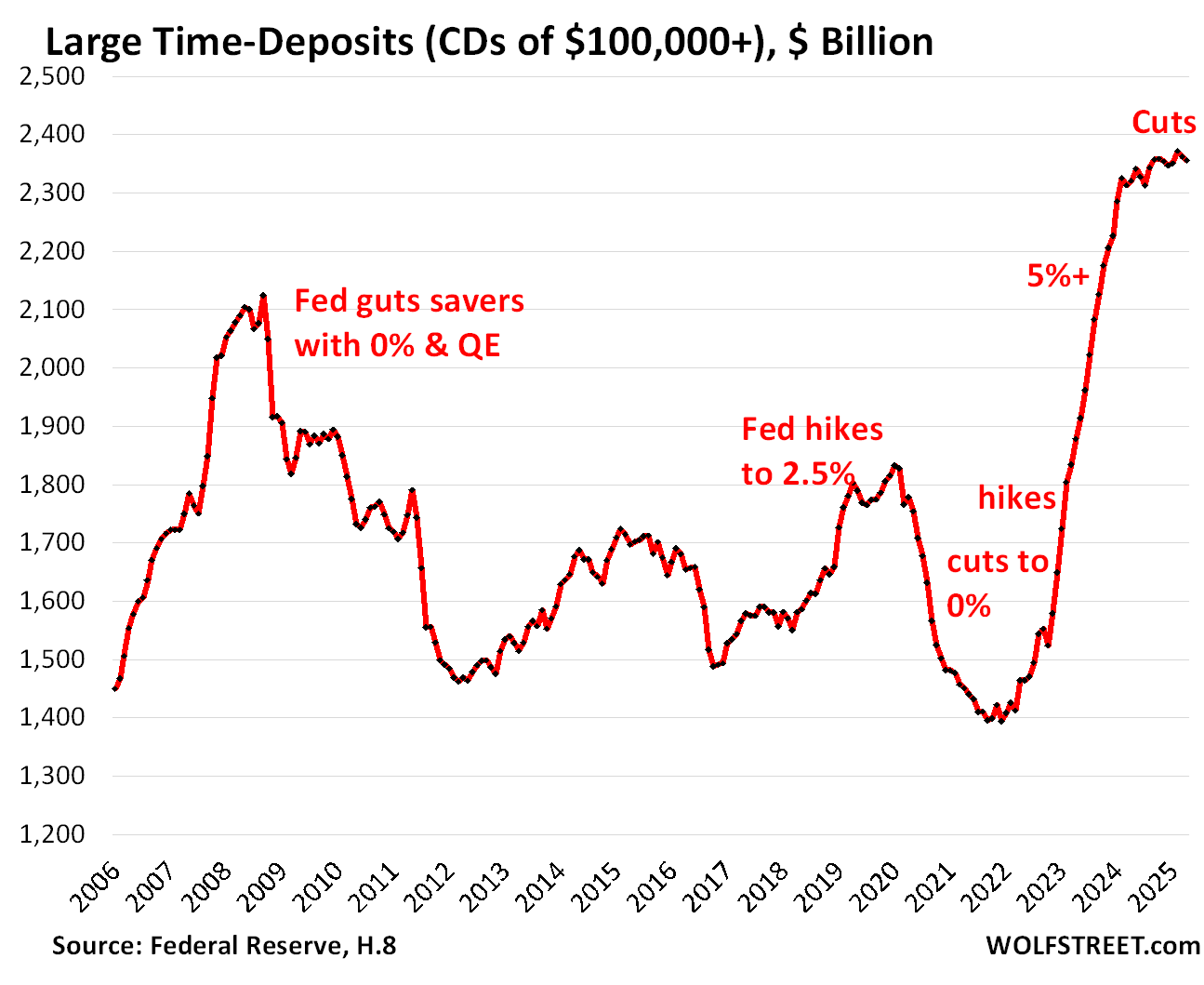

Large Time-Deposits (CDs of $100,000 or more) ticked down a hair over the past two months to $2.36 trillion in April, from the record in February, according to the Fed’s monthly banking data.

Since March 2022, when the rate hikes began, large time-deposits have surged by $943 billion.

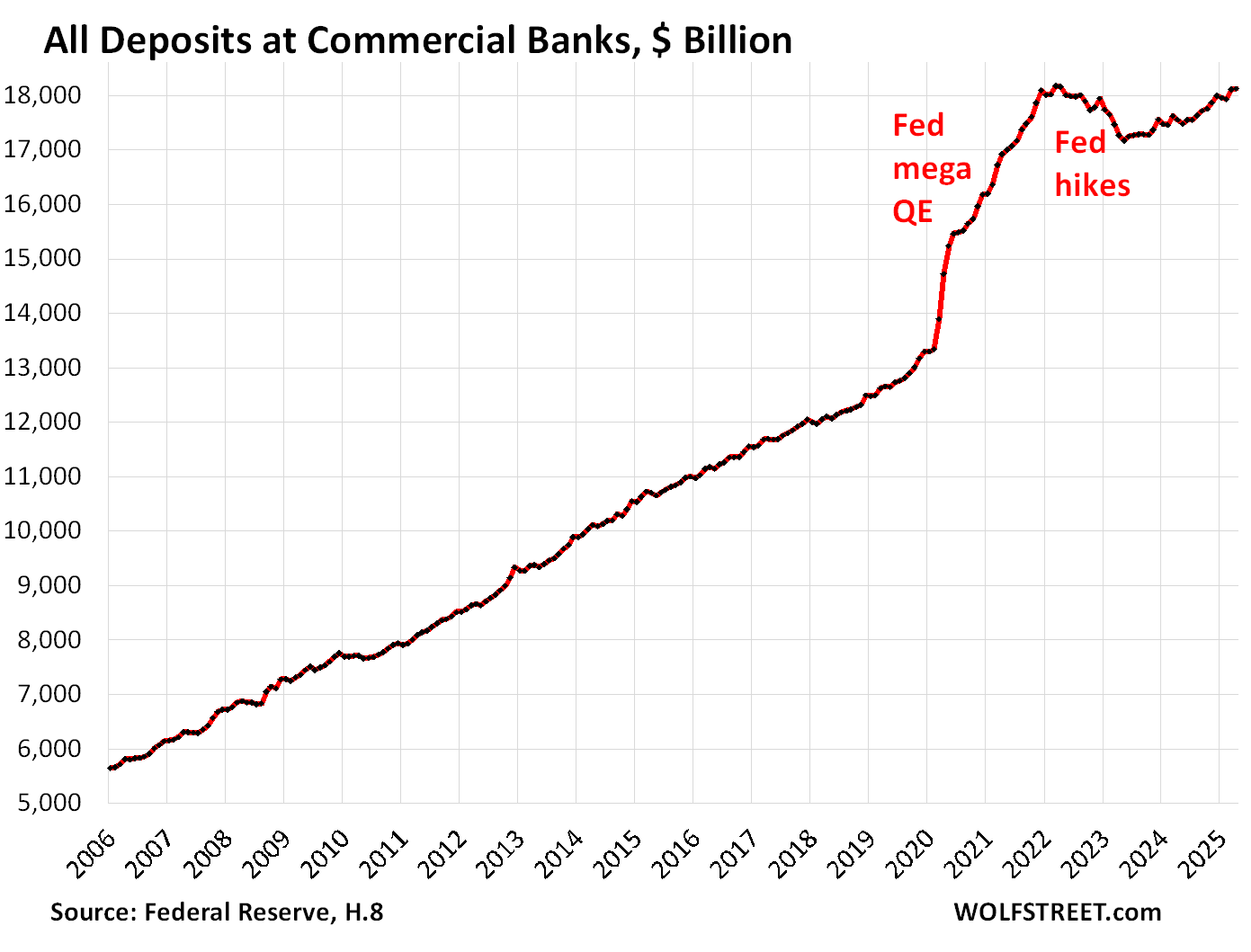

But CDs are only a small part of bank deposits. Total deposits at commercial banks are currently at $18.1 trillion, back where they’d been before the rate hikes. But they did drop by about $1 trillion from early 2022 through early 2023 as competing interest rates rose, and customers yanked their cash out. Higher deposits rates by banks then stopped the outflow and brough the cash back in.

As total deposits dropped by $1 trillion between early 2022 and early 2023, CD balances soared by $2 trillion during that time. What this means is that banks lost about $3 trillion in deposits in saving accounts and transaction accounts during that time.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

The post Money-Market Funds & CDs: Americans and their Piles of Interest-Earning Cash appeared first on Energy News Beat.

“}]]

Energy News Beat