[[{“value”:”

Tsunami of cash is still washing over money market funds. But banks’ fight for deposits is over.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

Interest rates paid by money market funds largely track short-term yields in the Treasury market and repo market, which money market funds invest in heavily. But interest rates paid by banks on their CDs largely reflect that individual bank’s need to hang on to cash from depositors or to get new cash from depositors, and lock it in for some time. And that need changes bank by bank based on circumstances.

And those circumstances have improved for banks, and so banks have reduced their CD rates faster than the yields of money market funds, and cash has shifted from CDs to money market funds, with CD balances declining and money market funds spiking from record to record.

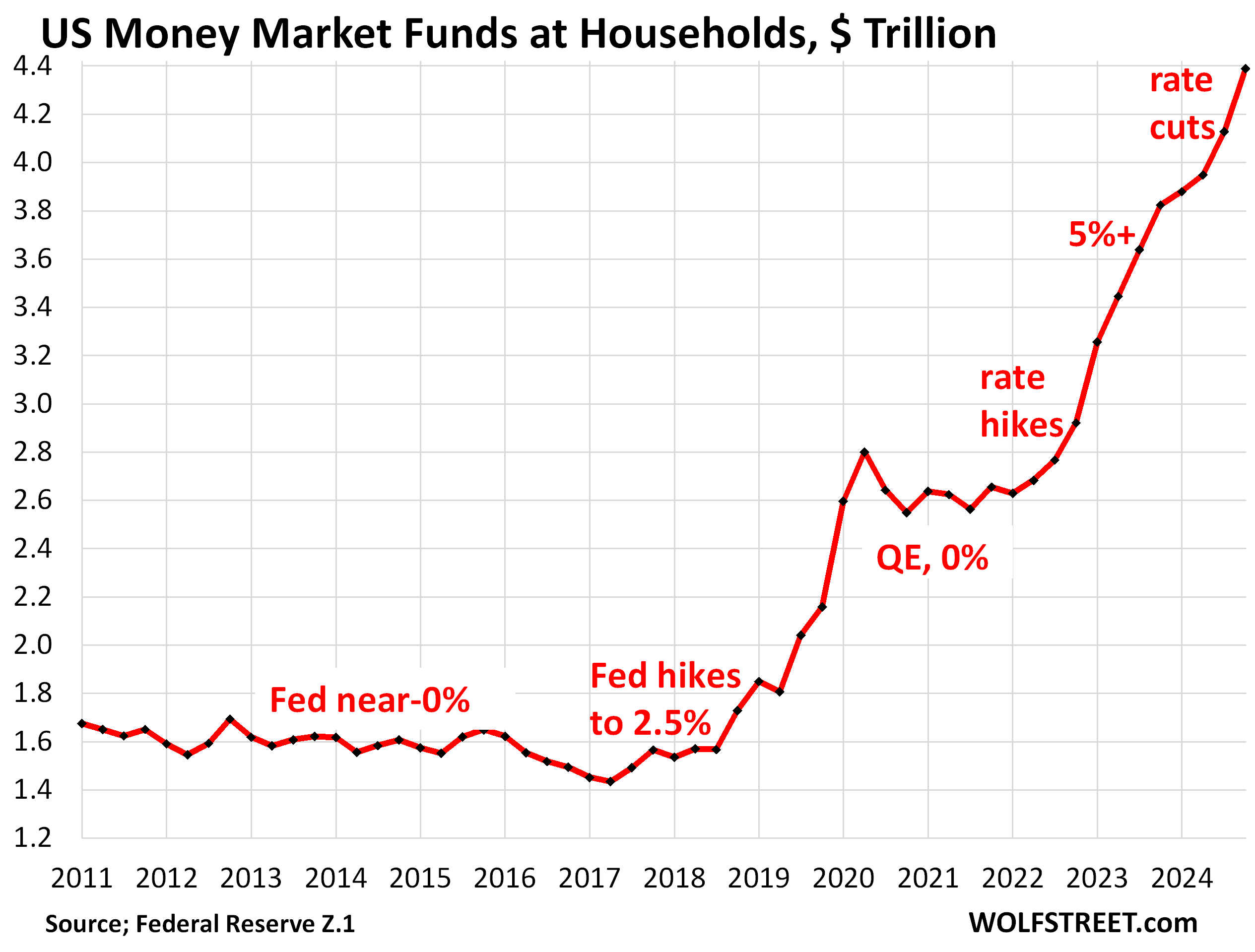

Balances in money market funds held by households at the end of Q4 spiked by $261 billion from the prior quarter, and by $569 billion year-over-year, to $4.39 trillion, according to the Fed’s quarterly Z1 Financial Accounts released today. Since Q1 2022, when the rate hikes began, balances have surged by $1.8 trillion.

This jump in MMF balances occurred even as the Fed has cut its policy rates by 100 basis points, and short-term Treasury yields have fallen about that much since last summer, with the three-month yield at about 4.3% currently. MMF yields have followed them and hover somewhere near 4.2%.

These MMF balances include retail MMFs that households buy directly from their broker or bank, and institutional MMFs that households hold indirectly through their employers, trustees, and fiduciaries who buy those funds on behalf of their clients, employees, or owners.

MMFs are mutual funds that invest in relatively safe short-term instruments, such as T-bills, high-grade commercial paper, high-grade asset-backed commercial paper, repos in the repo market, and repos with the Fed – the “Overnight Reverse Repos” (ON RRPs) that are now almost drained.

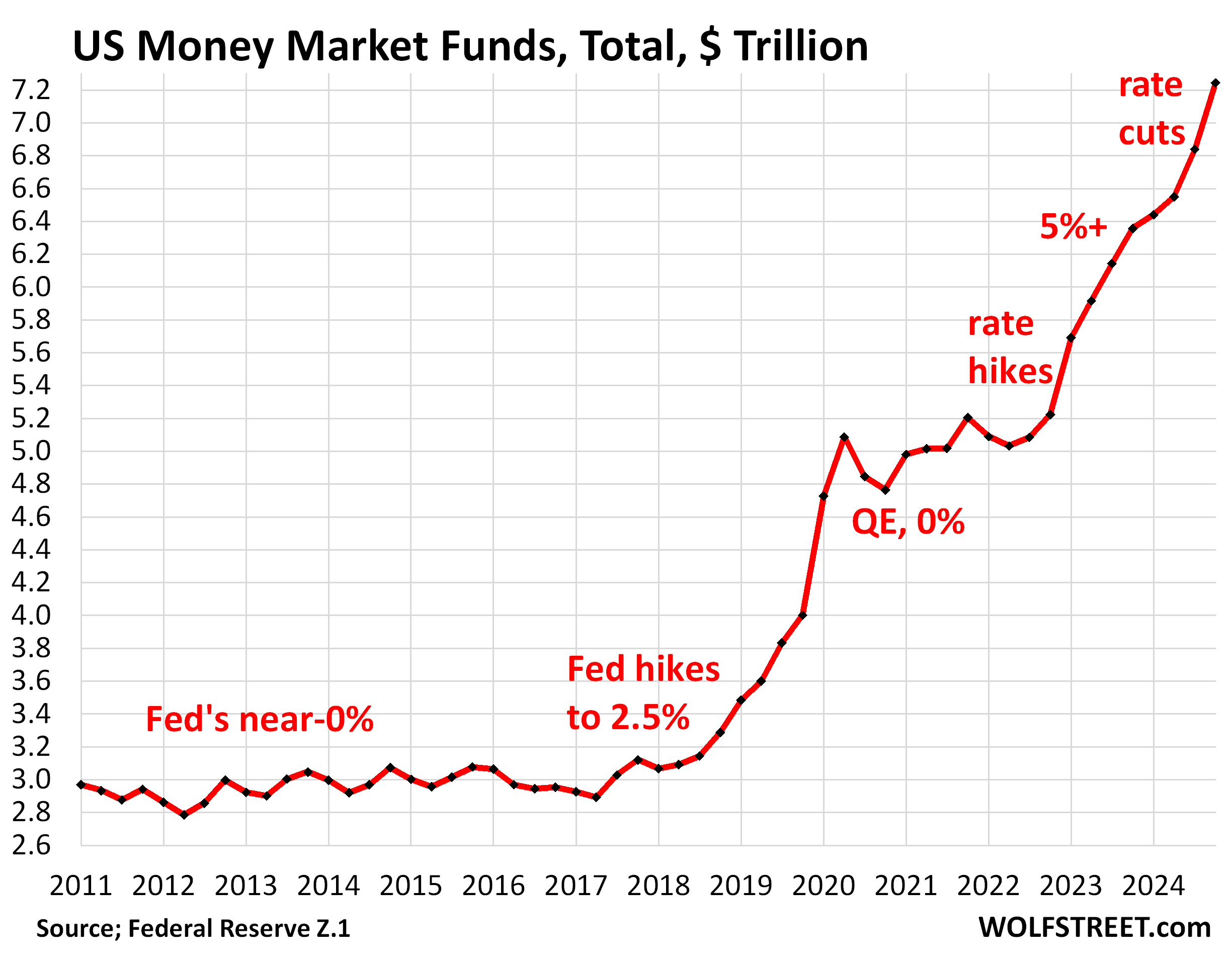

Total MMFs (those held by households and institutions) spiked by $404 billion in Q4 from Q3, and by $889 billion year-over-year to $7.24 trillion.

Since Q1 2022, balances have ballooned by $2.2 trillion. The influx continues despite the somewhat lower yields, likely attracting some cash from CDs, where banks have dialed back the rates more sharply.

Money market fund balances react to interest rates. When rates were near 0%, balances remained roughly stable for years at about $3 trillion. When the Fed hiked rates to ultimately 2.25% by December 2018, a $2 trillion tsunami of cash poured into MMFs. During the pandemic interest-rate repression, balances wobbled along a flat line. But when yields started rising again in 2022, another $2-trillion tsunami of cash washed over the funds, and continued through Q4 despite the somewhat lower yields:

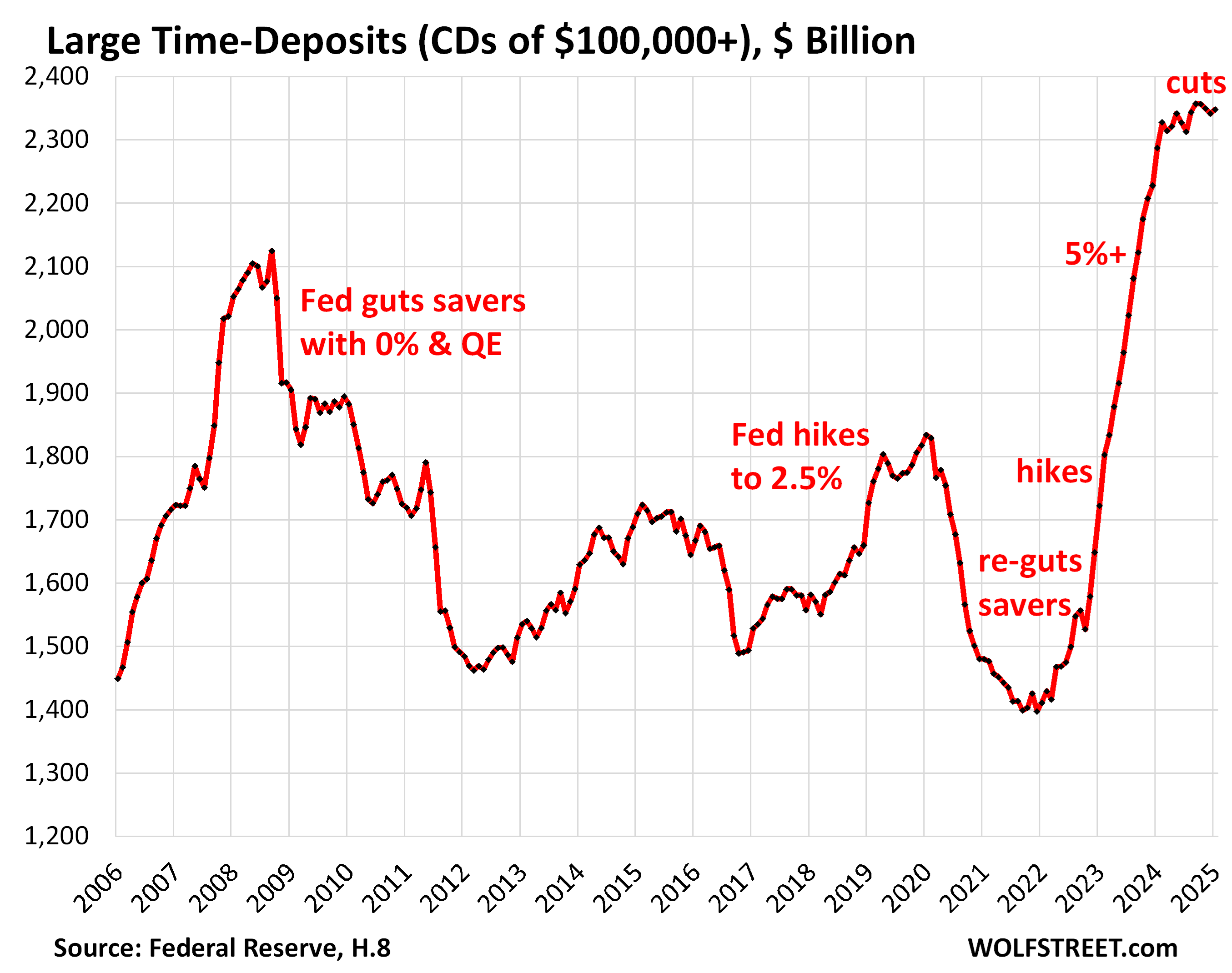

When MMF yields started rising in 2022, banks had to respond by offering higher yields on CDs and savings accounts to hang on to their existing deposits and to motivate new customers to put their cash into the bank.

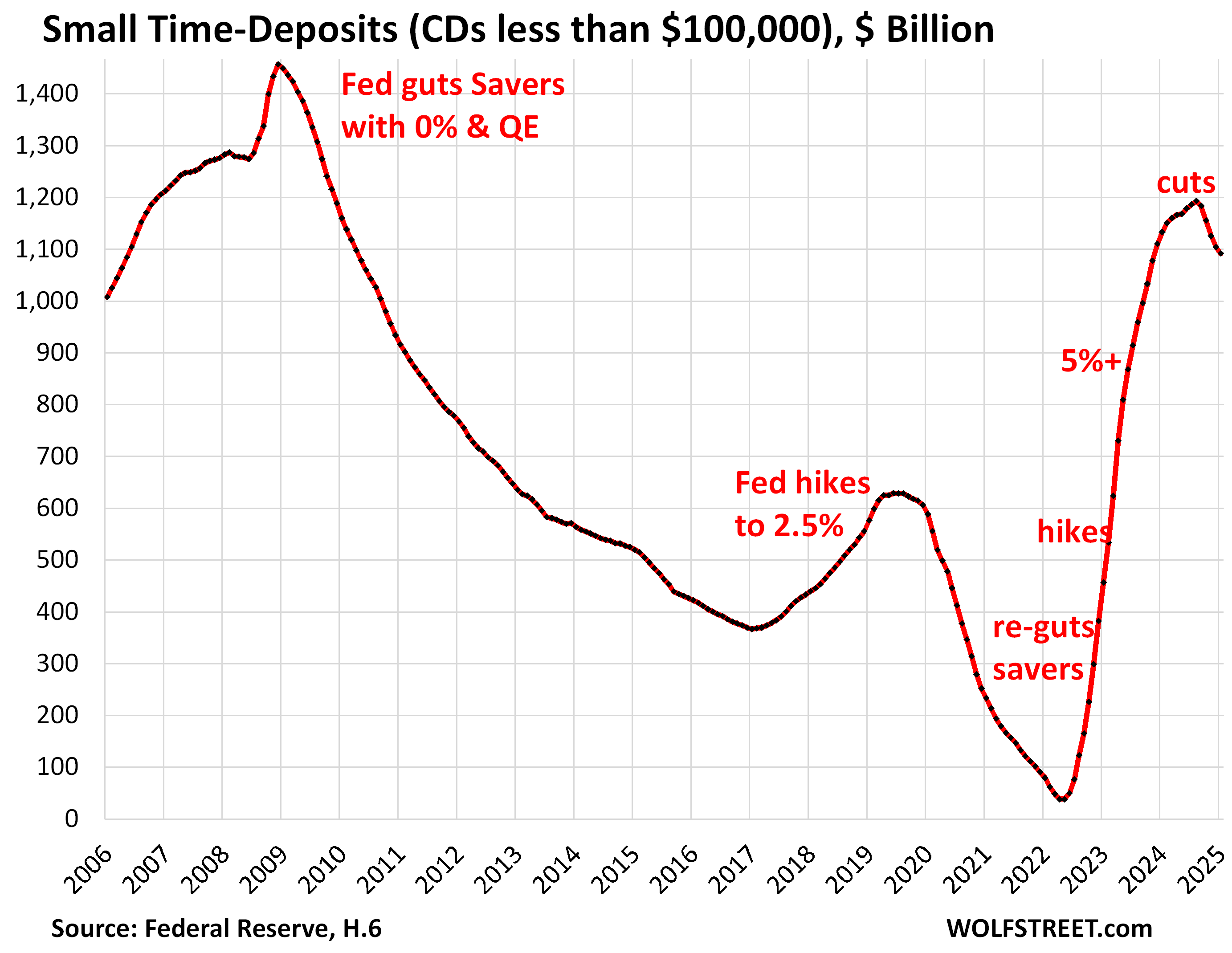

Small Time-Deposits (CDs of less than $100,000), after a huge surge from near zero in early 2022 to $1.19 trillion at the peak in August 2024, have dropped by $100 billion over the past five months, to $1.09 trillion in January, according to the Fed’s latest Money Stock Measures.

These small CDs reflect regular savers. When the Fed gutted their cash flow from savings in 2008, they got out of CDs. By mid-2022, these CD balances had plunged by 97%.

Paying higher interest rates on deposits – loans from customers to banks that form the primary funding of banks – increases banks’ cost of funding, and so they offer higher rates only carefully, and to some customers, such as new customers, and they try to keep as much of their deposits from existing customers at near 0% rates, such as checking accounts or low-yielding savings accounts, and all kinds of corporate accounts.

Banks count on deposits being generally “sticky,” especially in checking accounts and low-yield savings accounts, which means that when rates rise, a big portion of deposits doesn’t get the higher rates but stays at those banks anyway.

But some deposits did leave when yields rose, and banks had to deal with it by selectively offering higher interest rates, including through brokered CDs (CDs sold through a brokerage firm to that firm’s clients).

But over the past 12 months, the battle for deposits has largely settled down. Most banks have plenty of deposits, and have dialed back the yields they offer, and some unhappy customers have moved their cash to MMFs or directly to T-bills.

Large Time-Deposits (CDs of $100,000 or more), after a huge surge, have essentially flatlined since May 2024. In January, they ticked up to $2.35 trillion, according to the Fed’s monthly banking data.

Since March 2022, when the rate hikes began, large time-deposits surged by $932 billion, or by 67%:

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

The post Money Market Funds & CDs: Americans’ $11-Trillion in Cash, Not Trash, Much of it Still Earning 4%+ appeared first on Energy News Beat.

“}]]

Energy News Beat